Convocation Address: "Paint Yourself Into the Picture"

Sept. 4, 2025

Students, for this address, I craft my comments for you. About you. My goal is to do two things through this talk—1) invite you into a larger story, and 2) encourage you to act on that invitation. Invite and encourage.

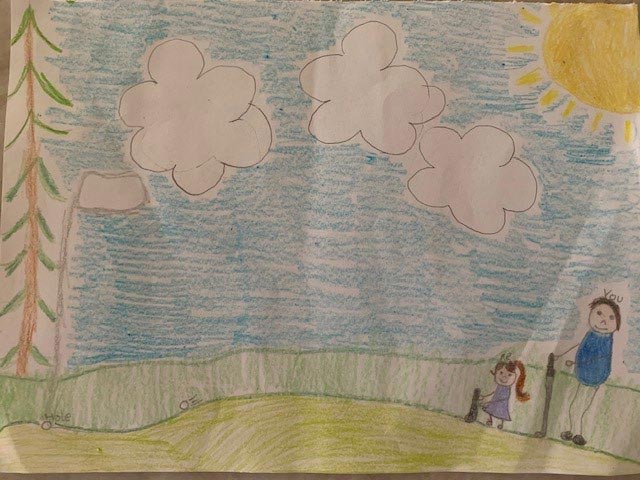

The very best part of my summer was when Anna, our 6-year-old granddaughter, walked through our front door and handed me this picture. Oh man, my heart was full. She drew this picture of herself on a golf course, where she and I have spent quite a bit of time. And do you see what she did? She drew herself AND she drew me into the picture! She could have drawn a whole lot of images of her own story, things important and meaningful and fun. But she drew this one where I was a participant in her life, her story. Anna and me, together, sharing something.

I have to pause here and point out some things in her photos and her form. That finish to the swing is perfect—front toe open about 30 degrees; stiff front leg; high hands; eyes level; belly button pointed straight ahead. On the putting green, eyes directly over the ball, back slightly hunched, although we need to get her about an inch closer to the ball. But I digress.

Anna's artwork got me to thinking about famous works of art in which the artist painted themselves into their work. Who did that? How did they do that? And why did they do that? I'm grateful for the input I got from Professor Meredith Shimizu and Professor Benny Fountain to help me answer those questions.

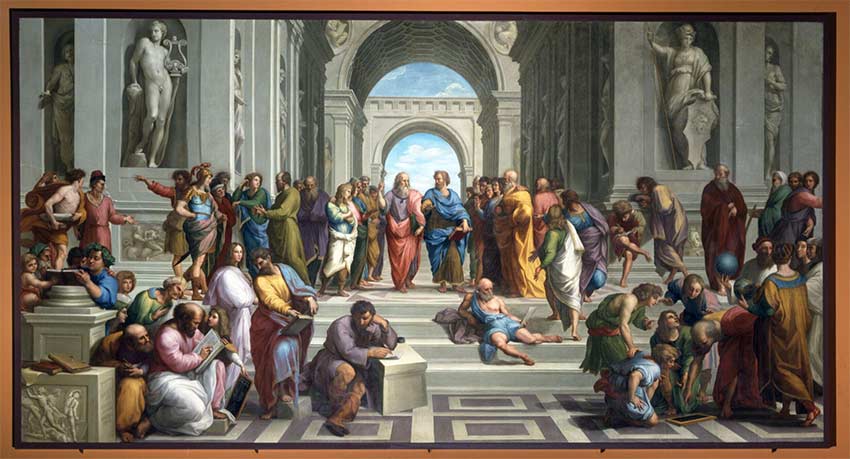

Maybe the most familiar case of an artist painting themselves into the picture is Rafael and The School of Athens. The setting is the Pope's library in Vatican City. There he is, on the right side of the fresco, making eye contact with the viewer. Rafael places himself among this renowned congregation of ancient philosophers, mathematicians and scientists, with people searching for knowledge, in the pursuit of ideas—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, Archimedes, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, among many others. There's something aspirational at work here. The artist seems to be sharing that he has skills and knowledge beyond only those of a painter. There's more to him than the role for which he is known. He's in the mix. Rafael is a philosopher with brush. A theologian with plaster.

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park, by Diego Rivera: This is a panoramic of the history and culture of Mexico. It covers a 400-year span, from Spanish conquest to the Mexican Revolution to mid-20th century when life was good. In this public park, Rivera paints himself as a 10-year-old boy with an adult face, holding the hand of La Catrina, a skeletal image of death. Standing among people like Cortez and Diaz, the artist is doing at least a couple of things, for sure: 1) showing the historical inequalities and struggles faced by everyday people; 2) the death figure is a neutralizing force; that in the end, when death comes to meet us, we are all equal, regardless of wealth or social status. But key here is how the artist is seen strolling through these eras of history, the skirmishes and conflicts. The artist, who is alive, is among Mexican ancestors still walking through life with him, even though they had passed. They are dead and gone, but still living—persons of influence, contribution, voices that we still hear, pay attention to, who inform our thinking and how we live.

Third of four: The Oxbow, by Thomas Cole, painted in 1836: Pictured here is a panorama of the Connecticut River Valley just after a thunderstorm. To the left, there's a dark, shattered tree trunk, rugged cliffs, a violent rain cloud—the land rich and untouched. To the right, the land is cultivated, with farmers and cows, aggressively reshaped and transformed from wild to settled. The land appears peaceful. There's even logging scars in the distance. And there, bottom middle, tiny, is the artist with his easel, painting the scene. Now, there are different interpretations about what he was trying to convey—is there a concern about nature and the destruction of a landscape created by God? Is that approaching storm symbolic of God's judgment and about to wash over the world? Or, perhaps, is this a picture of Manifest Destiny and the call to cultivate and rule. Maybe the sunshine points to the benefits of progress. I'm not here to pick an interpretation, favor one over the other, or mind-read the artist, who didn't tell us. What we can certainly say, though, is that the artist has engaged with what is going on around him. He is communicating the tensions between those worlds, and he draws us into the debate. He is not a mere bystander. Whatever is good, bad or indifferent in this painting, it is the environment where the artist lives and engages.

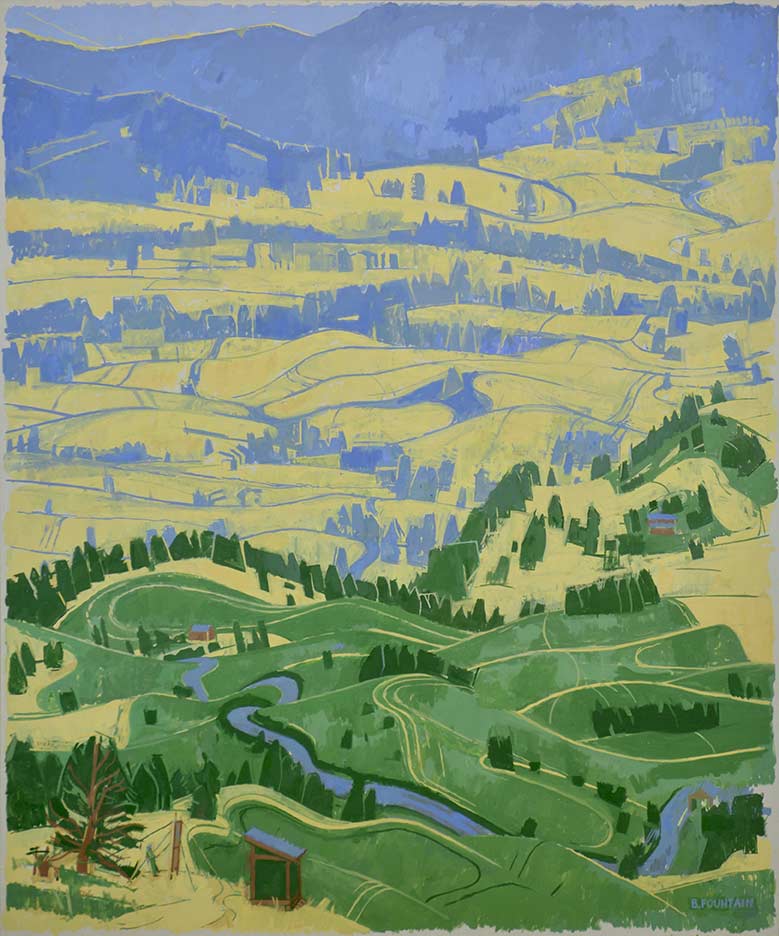

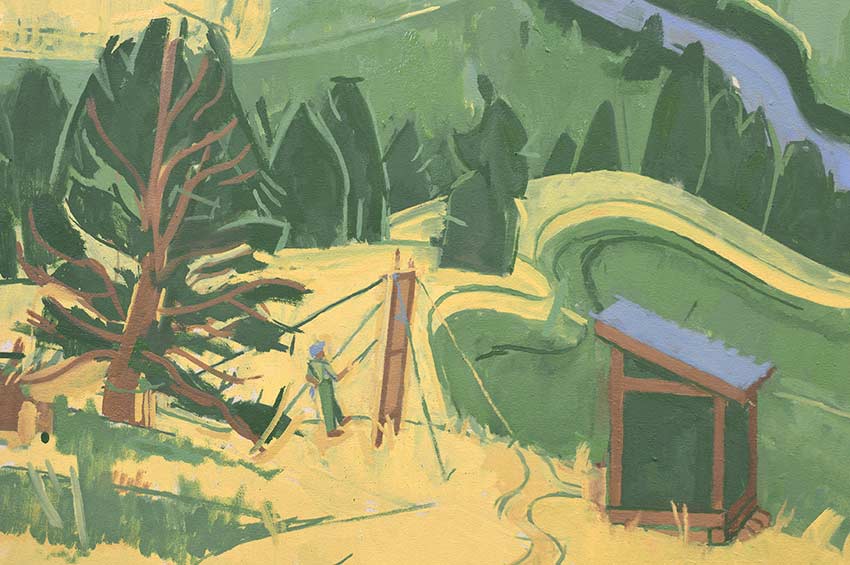

From Professor Benny Fountain, Hermit's Wealth. You can see Benny in the bottom corner of the painting, standing in the vast landscape, brush to canvas. He told me that this was actually like stepping back, outside of his work, as an author steps out of the flow of their life to write a memoir. It's about seeing one's life from further back, stepping out of the details for a broader view of the picture. In this case, Benny was wrestling with a big career decision and the uncertainties that came with it. At the beginning, there wasn't a plan to paint himself into the picture. But then while he was working, painting, he just showed up, right there in the work. In the midst of that angst and unknowns, he stepped back, he reflected upon where he was and the generosity of those who had made the moment possible—a farmer lent the spot; a father built the studio shack so that he could work and pray. And, so, Benny wrote to me, "The vast landscape is rich in yellow fields, blue shadows, and the curving rhythms of green Palouse hills. There is a figure at work in some forgotten hill of the world, receiving abundant provision. Manna in the wilderness."

To our Scripture texts for today: Dream on a Sunday Afternoon took me to Hebrews 12. "Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses..."

At Whitworth, our people and this mission exist, endure and thrive because of people who have demonstrated unwavering faith in God throughout their lives. They serve as encouraging examples for us. We occupy a university picture that includes people who have shaped the institution. It's not a passive crowd of witnesses, but an active, encouraging force. Students, you are part of a broader historical narrative, a sense of legacy and connection.

In our family home, and I suspect yours, there are family photos on your walls, ancestors with stories and legacies who inform who you are today. They've provided you an inheritance of sorts. The same is true at your university.

There's a best-ever-case of painting oneself in. Philippians 2 tells us that Jesus entered our picture. Catch the repetitiveness of the word "form" used in certain translations—"Who being in the very FORM of God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped; rather, He made Himself nothing, taking the FORM of a servant, being made in human likeness, and being found in the FORM of a man, He humbled himself, being obedient to death, even death on a cross."

This is such a complete description of who Jesus is and what he did—God, incarnate, servant, emptied himself—and also tells us His mind, his motivation, his innermost thoughts, where He pulls back the curtain. That news changes the way we look at everything, the way we think about everything.

He pitched his tent among us. In that human form, God entered into the world, our picture, living the human experience. He is with you at every moment.

Well, I could go on and on about the faculty, staff and administrator cloud of witnesses who have shaped the Whitworth painting. Students have, too.

About 35 years ago and six weeks into his first year, while walking out of chapel, Chris Murphy and a friend asked each other, "Are we just going to take and get for four years, or are we going to get involved?" The student club En Cristo was birthed and lives today, where every Saturday a group of students make and deliver sandwiches to those dealing with food insecurity.

Sarah Fox was a cross country runner who was never going to score a point in a meet. But, she's a Coach Toby Schwarz all-time favorite for what she brought to the team. She was a model worker, committed, and after every meet made a point of personally encouraging every single teammate, coach, athletic trainer and the bus driver! She was enriched by the community, but she gave away way more than she ever received.

Steve Badke was a really shy person. There was nothing remotely high-profile about him. But he loved to talk with fellow students, just sitting and chatting and wrestling with ideas. So, pretty often, he'd put out a feeler to the dorm that at 9 p.m. that night, anyone who wanted to swing by, the topic of the day was "X." Those lounge gatherings influenced the birth of PrimeTime meetings we have every night in your residence halls.

Brittney Peterson: Class of 2004, political science major, in my discussion group for an interdisciplinary class. So smart, so sharp, with an uncommon ability to formulate and express her thoughts. Whenever the class discussion was dead or couldn't gain traction, I'd just turn and ask, "What do you think, Brittney?" And class came alive.

Whoever had a moment with Pono Lopez had a better day. He just had this warm way about him. His presence in the hallway of a dorm lifted the entire floor. When I see him in two weeks, I'm going to tell him, again, what President Bill Robinson said about him: "Whitworth was good for Pono. And Pono was good for Whitworth."

These are alumni names, none of which you students would know. Very few of our faculty and staff would know them. It's unlikely any of them will make Dale Soden's next History of Whitworth book. But today, I am speaking about them. They each shaped a place while being shaped. They made choices to paint themselves in—I'm not saying that was easily done, nor that it came naturally. They might not have seen it in the moment. But my Whitworth picture includes them.

So, that invitation and encouragement for you.

Those artists made choices. You will, too.

I'm not suggesting you can paint yourself in everywhere. Maybe it'll just be here or there, and likely in little ways. Lots of possibilities for you. So, where do you see yourself?

You've accepted the invitation to be here. You've said "yes" to this educational feast. You've been presented with this opportunity to engage. So look for ways to paint yourself into the Whitworth picture. See yourself as part of this community. And while you're at it, paint yourself into the picture of the world. You are more than just a witness to what is going on around you. You are not merely spectators or museum-dwellers who stand back and observe. You have agency.

What, then, might I suggest you take from those paintings?

Like Rafael, paint yourself into the breadth and scope of what is offered. You will leave here well equipped, your whole person shaped, with something durable for an ever-changing world. And, like Rafael, know that you are far more than just a single aspect of your intellect, talents and personality.

Like Rivera, let's be mindful and grateful for the 136-year cloud of witnesses who shaped the university we are today. But we are not only a place shaped by generations of people before you. This is a place that you will help shape.

Like Cole, engage with classmates on the issues that confront the world, the things about which we might argue and hold differing opinions and perspectives, the things that afflict the world. We are witnesses and participants to all that is happening around us.

Like Fountain, stand back, be reflective. With this group of faculty and staff, and your friends, locate those people who can help you discern and process. Like the writer of a memoir, step back and see the flow of key moments of your life in the context of a meaningful whole. Process the full landscape of your picture and how your time at Whitworth is a key stretch of years.

And finally, know, and dwell upon, the incarnation, Jesus' entry into our picture, and what that means for each of us. It is that Jesus you will encounter throughout your Whitworth experience.

Because Jesus has come into our picture, there is reason for hope.

Students, the abundance of the Whitworth canvas awaits not just your brushstrokes, but your image within the picture. Amen.